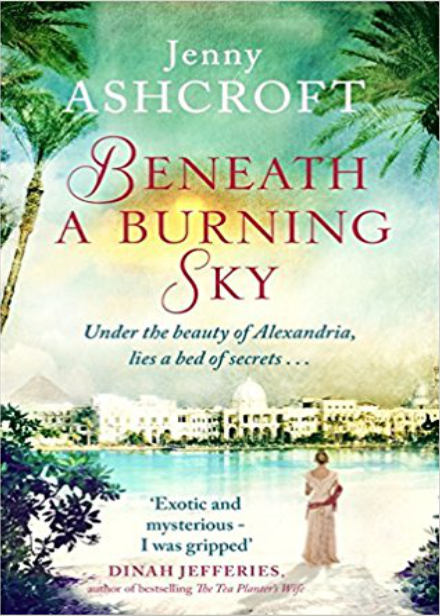

Beneath A Burning Sky Book Tour – Extract

[amazon_link id=”B01F44ODWM” target=”_blank” ] [/amazon_link]On the book tour for Jenny Ashcroft’s new book called ‘Beneath A Burning Sky’, sit back and enjoy an extract from the exotic tale.

[/amazon_link]On the book tour for Jenny Ashcroft’s new book called ‘Beneath A Burning Sky’, sit back and enjoy an extract from the exotic tale.

Central Alexandria, 30 June 1891

She reached for a wall, furniture, anything that might stop her falling. But there was nothing, and she fell, knees first, landing painfully on floorboards thick with dust. She pushed herself up, snapping her head this way, that way, disoriented by the speed with which everything was happening, straining to see. But after the fierce sunlight outside, the darkness swam and she could make out nothing but shadows and luminous spots.

She started to scream. A hand came over her mouth: strong, rough, forcing the sounds back into her. Men filled the room; three of them, no, four. Her breath came quick and short through her nose. She smelt sweat, garlic, a trace of hashish. Outside, she could hear the distant noise of the street: horses’ hooves, the trundle of a tram. The men talked in Arabic around her, so calm. It terrified her, how in control they sounded.

The hand on her mouth dropped.

‘What do you want?’ Her own voice was high, too strained, and unnaturally English. ‘I want to go. Let me go.’ She blinked, her eyes becoming used to the darkness. The room was all but empty; just a pile of crates in one corner, a table of glass bottles in another. The men were dressed in the white robes of locals. Their faces were concealed by rags.

Footsteps clicked in the cobbled alleyway outside; the scrape of what sounded like a handcart. She opened her mouth, screaming again, calling for help. The man before her looked down, his eyes dark, wholly empty. Bored, almost. He shook his head, and reached for one of the cloths covering his own face. Seeing what he intended, she arched her body away. ‘No. No, no, no.’ She scrambled to stand. Someone forced her down, the other shoved fabric covered in sweat and grime into her mouth. She gagged, choking, as more cloth was tied around her face

Barely able to breathe, with tears pouring down her face, she looked to the door. White cracks of daylight shone through it. The packed Rue Cherif Pasha was only a moment’s walk away. She lunged, making a break, but they jammed her back down to the floor. Her gown spread around her. Her head cracked. Why are you doing this to me? It came out as nothing but moans through the cloth.

She thought about her sister outside, still on the busy street. Perhaps in Draycott’s restaurant by now. The soldier, Fadil, too. Did he know? Would he come? Her mind moved to her home, all of them waiting. Especially him. Would he sense she was in trouble? Oh God, she couldn’t be here. This couldn’t be.

A man crossed to the centre of the room. He opened a trapdoor. Noxious smells rose up. She felt herself being hauled along. She shook her head, kicking. It was a useless protest. They reached the hole in the floor. She saw stone stairs, gaping black, and pulled away, thrashing, filled with new terror. Where are you? The question to her sister and Fadil screamed in her mind. Why aren’t you coming?

The first man disappeared into the floor. He seized her by her boots and pulled. Another pinned her arms to her side, heaving her along. As they carried her down, her body twisting and scraping along the rough brickwork, the others followed.

Find me. The trapdoor shut over her. Please, please. Find me.

Chapter one

Ramleh, Alexandria, March 1891

Olivia looked out across the bay. Sweat prickled on her forehead, down her spine. Her bathing pantaloons and tunic stuck to her skin. It was baking for March; everyone kept telling her so. You didn’t bring Blighty’s weather out with you then. (Really, how could she have?) The sun, even at just a little after nine, was biting; the kind of hot that after years of freezing English winters and disappointing summers she didn’t think she would ever become accustomed to. She rolled her tight shoulders. Her woollen costume moved with them, across her bruises, catching painfully on her cuts. She tensed her jaw on the urge to wince.

She never winced.

The Mediterranean lapped the rocks beneath her, a turquoise blanket that stretched out to the horizon and made home seem so far away. Around the headland, towards the city, long-tail boats scudded back to the harbour, sails full as fishermen returned to Alexandria’s morning markets, the waiting steam trains and donkey carts that would deliver their catch to Cairo, Luxor, a hundred other desert towns. The water flashed gold, speckled with light, inviting Olivia in.

She glanced back at the house. Her new husband, Alistair, stood on the veranda, ready for the office in his three-piece, the skin of his savagely elegant face as white as the veranda fencing surrounding him. He held a cup and saucer in hand, lingering over his morning tea: imported Ceylon leaves, a dash of milk from the kitchen cow, half a level spoon of sugar. (‘Level, Olivia, not heaped. Level.’) His gaze was fixed on her, watching. Always watching.

Olivia took a step. She felt rather than saw Alistair pause mid-sip, saucer held aloft, cup of Ceylon’s finest suspended. She flung herself forward and held her breath as first steaming air then cool water rushed through her layers, a balm to her burning skin. She dived deeper, lungs filling, fit to burst. For a sweet, submerged moment, she was invisible.

She broke the surface with a gasp, and swam out with swooping strokes. She was a confident swimmer, she’d learnt in the Solent as a child thanks to the icy dawn immersions that the mother superior at her boarding school had insisted on (excellent for your constitutions, girls, and your wicked souls). The distance between her and the shore quickly grew. It was only when her arms would take her no further that she rolled onto her back and let herself drift. Occasionally she turned her head towards the house, straining to make out Alistair’s ramrod form, imagining the tick of irritation in his eye.

It was a familiar routine by now. She’d been coming to this bay at the bottom of their garden every morning since Alistair had brought her to Alexandria three weeks ago; the fact that Alistair hated her doing it (‘I won’t descend to drag you out in front of the servants, but you should be in the house. With me. It’s improper, this gadding around in the water. Your skin is turning quite native.’) gave her reason enough to carry on. He made her suffer come nightfall, of course. With words first (‘What’s going on in your mind, Olivia? Have I not made myself clear?’), and then all the rest of it. But she wasn’t fool enough to believe that if she stopped, he would. He’d been finding reasons to punish her ever since the sodden winter’s day two months ago that she’d finally relented, given up on her hopeless search for an alternative, and married him. It wasn’t as though she’d swum the frozen Thames back then. No, it had been her melancholy at the ceremony that he’d taken her to account for that night. After that, it was the clothes she’d brought in her trunk for the P&O voyage to Alexandria (totally unsuitable, far too thick, for God’s sake. Was she listening? Was she?), then her laugh at the captain’s joke over dinner (frankly flirtatious), and so it went on.

Olivia closed her eyes, pushing the memories away. She floated, hair loose around her. The water muffled everything but her own breathing in her ears. The sun moved higher in the sky; she felt the tell-tale tightening of freckles cropping on her cheekbones and sighed inwardly, knowing her lady’s maid would insist on doses of lemon juice for nights to come.

She glanced again at the terrace and, seeing only space where Alistair had been, exhaled. She waited a few minutes more, enough time to ensure he’d really left for the day, off to the headquarters of his cotton export business in the city, then made her way back in. As she sliced through the soft swell, her unhappiness weighing bluntly inside her, she consoled herself with the thought that her older sister, Clara, would be calling soon. She came every morn- ing, riding over by carriage from her own home up the coast.

Sometimes she was alone, more often than not she brought her sons, Ralph and little Gus. Olivia still got a jolt, seeing them all. Clara especially. Real again, at last. For fifteen long years, ever since the two of them had been forced to leave their childhood home of Cairo for England following the death of their parents, they’d been kept apart. They’d had no communication – their grandmother had made sure of that: not a letter, not a word. Olivia hadn’t even known Clara was living back in Egypt, the land they’d been born in, until Alistair had arrived on her doorstep in London and told her. Clara had been little more than a shadow to her; that dull ache of knowing she existed somewhere in the world, but with no clue as to where. And a memory, just one, of the day their grand- mother – full of hate towards their dead mother and determined to exact her revenge, as though death wasn’t enough – had torn them apart: that freezing January morning at Tyneside docks, back when Olivia was eight, Clara fourteen, and which Olivia tried, very hard, never to think about.

She didn’t think about it now as she pulled herself from the sea, clambering out of the water. Wrapping herself in her bath sheet, she turned, picking her way over the rocks and into the garden. As she padded up the lawn towards the house, grass stuck to her toes. Water evaporated from her skin, leaving salty snail-trails on the unladylike tan of her forearms. The villa loomed large before her, a palm-fringed palace. Its terracotta walls were laced with jasmine, the shutters flung open in every room revealing the shadows of servants moving within. Olivia passed into its stultifying shade.

On the way to the stairs, she paused at the door to the boarder’s room – a cavalry officer by the name of Captain Edward Bertram. He’d been staying with Alistair, a business associate of his father’s, for years. It wasn’t an unusual arrangement – all British officers rented private rooms in Alex, there was no great garrison here as there was in Cairo – but Olivia had yet to meet this houseguest. He’d been away ever since she arrived.

Today, though, the door to his room was ajar and two maids chattered within. Olivia asked what they were doing, and they replied that Sir Sheldon (they all called Alistair so, even though he wasn’t a ‘Sir’ anything; it was the way of Egyptian servants with their masters) had asked for the room to be readied for the captain’s return. Word had come that he’d be back that night.

Olivia shrugged, unsurprised by Alistair not bothering to men- tion it to her, and only mildly curious to meet this captain at last. Her life was so full of strangers these days, what difference would one more make?

She carried on upstairs, her thoughts fixed on getting ready for Clara. By the time she reached her bedroom she’d all but forgotten Captain Edward Bertram was on his way home.

Edward dropped down into his seat as the Alexandria Express creaked into motion, steam filling the air beneath the vaulted iron roof of Cairo’s central station. He pulled his case of cig- arettes from his jacket and lit one, inhaling slowly as the train chugged out to the fierce daylight beyond. As it picked up speed, funnel blowing, the beggar children who lived in the surround- ing slums – blackened urchins with round eyes and mouths that were too big for their faces – swarmed alongside the carriages, hands outstretched. Edward stood, throwing what coins he had for them, then winced as one leapt for a window and was pushed from within, landing, a ball of scrawny limbs, in the rocks and dirt. He came to a halt just shy of the rails, but was up within the instant, ready for more.

Edward shook his head, staring after him.

‘Serves him right,’ came a bored voice from opposite; a sunburnt man in a top hat and three-piece suit. ‘You shouldn’t have encour- aged them, you know.’

‘Yes.’ Edward smiled tightly, reclaiming his seat. ‘Lazy buggers.’ ‘Just so.’

‘Perhaps you have a factory somewhere you could put them to work in? Some sixteen-hour shifts would do them the power of good.’

The man narrowed his eyes. ‘I’m in the civil service.’

Edward laughed shortly. ‘Of course you are.’ He took another drag on his cigarette, stretching his legs out before him, and turned to stare at the flat-roofed slums of Cairo passing by, letting the man know the conversation was closed.

The past weeks at the garrison training recruits had been hell- ish. He would have been pleased to be getting away from it – those baking days in the fly-infested boardroom, the lectures on the basics of the men’s role (desert reconnaissance, border patrols, self-important circuits around town to remind everyone who was boss, and so on) – had he not been so depressed at the prospect of returning to Alexandria.

He’d asked for the month in Cairo as a favour from his colonel, Tom Carter, to get him out of town; he’d been disgusted by the callous way Alistair had gone off to England to fetch Clara’s sister for his wife, incredulous that – more than a decade on from Clara’s humiliation of Alistair, during that London season only ever spoken of in whispers – Alistair should have redressed the balance with such calculated determination. For Edward had no doubt that’s what it was all about, that Alistair’s choice of wife had far more to do with Clara than with Clara’s sister. But even he, who’d observed Alistair’s fixation with Clara many times in the three years he’d been living with him – wondering how the hell Clara tolerated his pale eyes on her at parties, the curl in his lip whenever she spoke – had never imagined it would cause him to stoop so low. He simply hadn’t trusted himself to be present when Alistair returned from London, dragging the new Mrs Sheldon with him. And the time away in Cairo had made him see just how sick he’d become of life in Egypt; not just his role – the drills, the endless drills, the desert trips and constant monitoring of locals who’d never asked to be governed in the first place – but living with Alistair too.

He’d wired Tom. Any chance of my getting out and going home before my commission is up?

None, Tom had replied. Everything all right, old man?

Not really, wrote Edward. How about a transfer?

Tom had set the process in motion: a promotion to major, in Jaipur. It would take a while, but it was going through. Edward wasn’t a fool, he knew that in the end life in India would be more of the same. But since he apparently had no choice but to serve out his time in the cavalry, he might as well do it somewhere new.

After all these years in Egypt, he needed a change of scene. Jaipur would feel different. For a while at least.

He turned to the window, watching as the city gave way to desert, the dunes rolling past. He drew on his cigarette, paper crackling, and exhaled; smoke spiralled through the open window, mixing with the white haze of the desert beyond.

He was right to go.

Really, when all was said and done, what was there to keep him in Egypt?

‘Livvy!’ Clara called out from beneath the fig tree. ‘I hope you don’t mind us making ourselves at home?’ She smiled, cheeks dimpling.

She’d laid out a tartan rug in the shade and was sitting, lace skirts cushioned around her, with baby Gus gurgling on her lap. Clara’s older boy, eight-year-old Ralph, was on the lawn beside them, freckled face serious, stockinged legs braced, hammering hoopla pegs into the lawn. He looked up at Olivia and waved his hammer. ‘Hello, Aunt Livvy.’

Olivia waved back. As she crossed the grass towards them all, Clara gestured at a wicker basket. ‘Oranges,’ she said. ‘I brought them from my garden, they’re out early this year. All the warm weather. Try one, Livvy, they’re positively bursting with sunshine.’

Olivia said she was fine, thank you, she’d never really liked oranges.

Clara’s brow creased. ‘You used to . . . ’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Yes,’ Clara said, ‘Mama grew them too. I remember you eating them when you were little.’

‘Really?’ Olivia frowned, trying to recall ever doing such a thing.

But there was nothing there, just a blank. All of her childhood before she and Clara were separated was just that. The morning they arrived in England after their parents died, those freezing London docks, Clara’s sobbing face, her own desperate fear as her grand- mother told her where she must go; there was a wall in her mind, blocking out everything behind it: her early years back in Cairo, Clara as a child, their parents’ faces, the sound of their voices . . . Gone. It was Clara who held all the memories; she was passing them on to Olivia one by one. Your education.

‘I used to peel the white bits for you,’ Clara said now, staring down at an orange. ‘You liked it, I promise.’

Olivia sighed, said she was sure she had. She dropped down onto the blanket, landing with a soft thud. She leant over Gus, tickling him under the chin. He squirmed, rustling against Clara’s gown. Leaves cast shadows on his face. So dark, this little man, as though he’d sun-baked in the womb. He eyed Olivia warily. ‘Don’t worry,’ she said, ‘I’m not going to try and take you from your mama.’ She tickled him again. ‘I wouldn’t dare.’ He screamed blue murder with everyone except Clara.

Clara stroked the curve of his olive cheek. ‘Little monster,’ she said softly.

A maid came out with a jug of minted water, some pistachio bis- cuits. They drank and nibbled whilst Ralph played. Clara peeled an orange, dripping juice into Gus’s mouth. Every time Ralph landed a hoop on a peg, he’d turn, and Clara would exclaim, making him beam.

The longer Clara watched him though, her own expression shifted, became heavy.

‘Are you all right?’ Olivia asked.

‘Yes,’ she said distractedly, ‘of course.’

‘You look sad.’

‘No, no, not at all. I’m splendid.’

‘You’re not.’ Olivia nudged her. ‘You turn ever so British when you’re only pretending to be all right.’

‘Do I?’ Clara laughed at that.

‘So?’ Olivia prompted her.

She shrugged, eyes on Ralph. ‘I was just thinking of him going

off to school in England, that’s all. July seems too soon.’

‘Have you told him yet that he’s going?’

‘No. I can’t do it. Jeremy doesn’t seem to want to either. He’s obviously hoping I’ll give in first.’ A dent formed on her brow. ‘Foul man.’

It was hardly unusual for Clara to speak of her husband so. She might have told Olivia that she’d felt differently once, years ago, back when she first met Jeremy during that London season – Jeremy, a joint partner in Alistair’s vast network of cotton plantations, had been in England with Alistair on business, and Clara, introduced to them both at a debutante ball, had (to Alistair’s lasting chagrin) fallen for Jeremy’s charms instantly – but these days she was always calling him foul. Olivia struggled to see it herself.

Jeremy was so kind to her, stopping to chat whenever he called at the house, enquiring as to whether she was bearing up with the homesickness, not finding the damned heat too intoler- able, the loneliness too hard.

Olivia always assured him that she was well (a lie that came like breathing; a legacy of the nuns who’d beaten the habit of betraying upset from her long ago. Self-pity is a sin. And what do sinners need? Yes, that’s right . . .) but she could tell from Jeremy’s grimace that he knew she wasn’t, that she hadn’t been ever since Alistair had convinced her grandmother to exer- cise her legal rights as guardian, cut her off from her inheritance, leave her destitute if she didn’t agree to marry him. That or send her back to the convent as a nun. She couldn’t help but be grateful to Jeremy for his understanding; if they’d lived in a world where thoughts really were all that counted, his silent empathy would have meant a great deal.

He could be distant with Clara though, she supposed; the two of them rarely seemed to talk, other than about the children.

Still, Olivia would take distance over the alternative any day of the week.

‘I want to keep Ralphy back another year,’ said Clara. ‘He’s still such a baby. My baby.’ She paused, frown deepening. ‘I’d keep him with me for ever.’

‘Then why don’t you?’

‘Because Jeremy won’t have it. He says it’s not fair on him, that we’ve already held him up, and it will be harder on Ralph in the long run if we do it again.’

Ralph collected his hoops, threading them onto his chubby arm. He caught Olivia’s eye and smiled. She, thinking of the brutal lone- liness awaiting him, managed barely a grimace in response.

Clara said, ‘Grandmama’s written. She wants to come over at the start of July, take Ralphy back herself. She’s booked the voyage.’

Olivia turned, aghast.

‘I know,’ said Clara, looking as desolate as Olivia felt at the pros- pect. ‘I’ve written to say she mustn’t, but I’m not sure she’ll have any of it.’ She raised her face to the sky, eyes scrunched with the effort of her thoughts. ‘I’d take Ralph myself, but Gus is so little for the journey, and I can’t leave him here, it’s too hard.’

Why?’ Olivia asked. ‘Why is it hard?’

Clara didn’t answer.

Olivia said, ‘You have to do something, Clara. You can’t let that witch take Ralph.’

Still, nothing.

Olivia filled her cheeks with air and let the breath out. Even the thought of Mildred made her feel ill. It wasn’t just the way she’d helped Alistair blackmail her into marriage, the delight with which she’d reminded Olivia that given her parents had left no will, she’d won complete control of Olivia’s person, her money, until she wed. I mean it, Olivia, I’ll see you back in that convent, don’t think I won’t. Who else can you go to for help? Your friends have no means. You haven’t seen your sister in years, I expect she’s forgotten all about you. It was everything else Mildred had done, back when Olivia and Clara were children. Olivia could picture her even now at those docks, dressed in black taffeta, waiting at the foot of the gangplank when she and Clara got off the ship after their journey from Cairo. She could see the fog blowing from her mouth, hear the satisfaction in her thin voice as she told Clara she’d be taking her home to Mayfair, young Olivia here had somewhere else to be, a convent school in fact. Say goodbye quickly now. The nuns are waiting, Olivia . . . And then, what had hap- pened next . . . No. Olivia drew breath.

She returned her attention to Clara. ‘You can’t let her come,’ she said again. ‘I can’t face it.’

‘Nor can I.’

Neither of them spoke for a while after that. Clara fiddled at Gus’s frock, then peeled another orange, only to let it sit, uneaten, by her side. Ralph threw more hoops. Olivia batted at the flies.

At length Clara asked Olivia, as she always did, how things had been with Alistair since yesterday. Olivia lied, as she always did, and said fine, or fair at any rate, and received the usual small smile: pained, disbelieving.

Olivia picked at a blade of grass. She could feel Clara watching her, waiting for her to say more. But Olivia didn’t know how to begin to put words to her marriage. And really, what was the point? What

could Clara do? It wasn’t as though Alistair would ever let her leave; he reminded her nightly that he’d track her down if she ever tried it, that he’d have her in the madhouse as a lunatic before he released her from her vows.

Olivia pulled at the grass, making it snap. Ralph, giving up on his hoops, loped over and dropped down by her side. She tried for a smile, ruffled his tawny hair.

Clara reached over, taking hold of her fingers, squeezing. ‘I’m so sorry,’ she said, for the hundredth time.

‘If I’d only known what he was planning when he left for England, I could have sent money, helped. Simply forced Grandmama to tell me where you were. But he never breathed a word of it, not to me, not to Jeremy . . . ’

‘It’s not your fault,’ said Olivia.

‘I feel as if it is. What I did to him all those years ago, Jeremy too. His friend. He’s never let it go, and now you’re paying for it.’

Olivia looked down the lawn towards the bay. ‘I don’t want to be here when he comes home tonight.’ She heard the words before she realised she was going to speak them. She gave a self-conscious laugh, awkward even at this small honesty.

Clara tightened her hand. ‘Leave a note,’ she said. ‘Tell Alistair you’re meeting me for dinner. Jeremy mentioned they have a big contract on, they’ll be working late. If you get away from here by seven you’ll miss him. I’ll book a table in the Greek Quarter, you haven’t been to Sabia’s yet. I might be a little late, I have an errand to run, but you can always have a drink whilst you wait.’

Olivia nodded, relieved.

Edward’s man, Fadil, was waiting outside Alex station, wiry in his oversized khaki, bald head glinting in the late afternoon sun. He had both their horses with him. Edward took his own stallion, patting his silky flank, then shook Fadil’s hand, pleased to see him after these weeks away. It wasn’t often they were parted.

Fadil had been working for Edward ever since he’d come to Egypt, back when the British Protectorate was first established in ’82. He was an excellent batman as well as soldier, and Edward normally took

im everywhere. But he’d insisted he’d cope alone in Cairo on this occasion. Lines were rigidly drawn at the garrison there, the quar- ters for native soldiers were rank; Edward wouldn’t stable his horse in them, let alone subject Fadil to the filth.

He hadn’t written to tell Fadil that he was going to India. He was ashamed of the secrecy, but he couldn’t face it, not yet. He’d asked Tom to keep the news from the rest of the men too. He hated good- byes; until his date for going was locked, he wouldn’t start them.

He asked Fadil how life had been this past month. Fadil said fine, normal. Edward enquired after each of his lieutenants, Fadil told him they were well, drilling every day.

‘Naturally,’ said Edward.

Fadil held out a note. ‘From the colonel, sayed.’

Edward took it, stifling a yawn. It was the stuffy carriage, it had jaded him. His eyes moved over Tom’s scrawled hand.

Immy’s furious about your transfer, all my fault apparently. She says I’m to take you both to dinner tonight to apologise for arranging it. Meet us at Sabia’s at seven. Will be good to see you, old man.

Edward smiled, pleased in spite of his tiredness, at the prospect of spending the evening with Tom and his wife. He decided to go to the parade ground to change; his tails had been freshly pressed back in Cairo, he had everything he needed with him. He couldn’t stomach returning to Alistair’s just yet.

He swung into the saddle and rode from the station with Fadil by his side. As they clopped through the stuccoed city centre, Edward stared at the odd remnant of a shattered wall, the broken ruins where offices had once stood. Even a decade on, the rubble still made him stop, pause: these lingering marks of the damage done by the Royal Navy’s guns, back when they’d had to pound Alex with cannons before the ruling khedive would allow them in to set up British rule. A reluctant intervention, so the story went, when political unrest in the country ran out of all control – government coups, riots, and so on. Everyone knew it had been as much to do with the allure of Egypt’s rich cotton fields, cheap labour and easy access to the East.

It wouldn’t do to speak of that, of course.

Edward kicked his horse on, down into winding streets that led to the harbour. They were packed, even at this late hour, the cobbles hemmed in by stone dwellings, market stalls, fruit shops and bakeries. The air was rich with the tang of ripe fruit, spices and onions sweating in oil. Edward wove this way and that, avoid- ing the crowds. As he and Fadil reached the coast road, though, Edward spurred them both on into a gallop, relieved to be in the open, moving. He gave his horse the reins and drank in the deep blue of the Mediterranean, its colour such a contrast to Cairo’s dust. He kicked. Faster. A warm wind rushed around him, raw with salt. Desert blossom spread over the sandbanks lining the road. Edward breathed deep on the scent, the fresh air, relishing it: a short burst of life before Alex crackled and withered in the deadening summer heat.

He arrived at the restaurant early and lingered outside, looking down the wide avenue. It was a rich part of town, full of the villas of wealthy Greek families who’d moved across the sea to make Alex their home over the centuries. The pavements had more than one well-dressed couple strolling along them. Cypress trees swayed lazily in the balmy air; the sun was only just setting. Edward, legs still twitching from being on the train for so long, decided on a walk himself.

It was then that he saw her, crossing the road from where several carriages were parked. She was dressed in a sleeveless blue gown, and she was tanned; unusually so.

It was the first thing he noticed.

She looked up at the restaurant sign, eyes registering its name. She pressed her tooth to her bottom lip.

‘Are you all right?’ he asked, since he had to say something. ‘Not lost?’

‘Not lost,’ she said. ‘Just making sure I’m in the right place.’

Her voice was the second thing he noticed: soft, warm; nothing like the cut-glass tones he was used to.

She carried on in.

And he stared after her.

He could hardly stop himself looking.

Like what you read? You can buy [amazon_link id=”B01F44ODWM” target=”_blank” ]Beneath a Burning Sky from Amazon [/amazon_link] and is available to buy from good bookshops.

Leave a Reply